Understanding Trends in the History of the World Chess Championship

What better way to get excited for the upcoming championship this year than with some data?

Ahh November, when winter sets in and people’s minds (at least in America) start moving towards turkey and cranberry sauce. Meanwhile chess fans are getting ready for an event they anticipate with less and less excitement each iteration — the FIDE World Chess Championship. The reason for this is simple — the best player in the world hasn’t played in the last two.

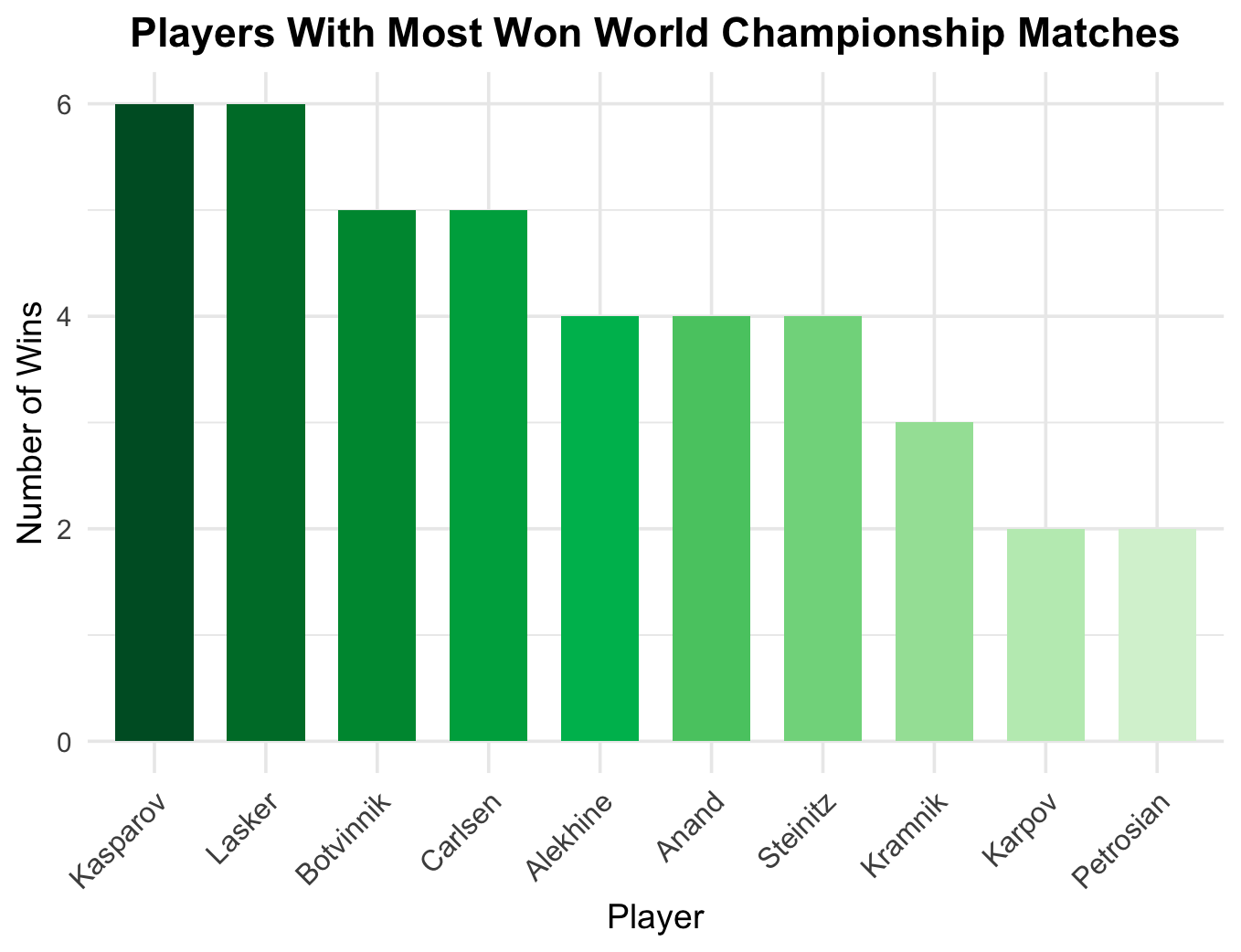

Magnus Carlsen is still the highest rated player in classical chess by a considerable margin. In 2022, after his 5th World Championship win in 8 years, he made the unprecedented decision to give up his title and allow others to duke it out for the title. True to the times, he made his initial announcement on his podcast. Carlsen explained: “I don't particularly like it, and although I'm sure a match would be interesting for historical reasons and all of that, I don't have any inclinations to play and I will simply not play the match.”

For the previous match and this upcoming one that will miss Magnus, many critics have emerged asking logical questions. For example, “How can we call someone the world champion if they didn’t beat the world’s best chess player?”

To that I say phooey! The show must go on, and chess fans still have a lot to get excited about this year. The 18 year old challenger Gukesh Dommaraju (who often goes by the novelistic Gukesh D.) is the youngest player in the history of chess to partake in a match for the world title. If he wins, as he is the massive favorite to do, he will become the youngest ever chess champion in its entire history!

Speaking of History…

As Carlsen said, the history of chess championships is a big draw for the event these days. It is long and storied. The first worldwide accepted chess championship was held in 1886. Five years before James Naismith hung peach baskets on the walls of a high school gymnasium and invented basketball. 71 years before the first Super Bowl, and 44 years before the first UEFA World Cup.

This is because chess is one of the oldest games that are still widely enjoyed today. A treatise on the principles of chess written by Spanish priest Ruy López de Segura in 1561 confirms to historians that the modern rules of chess were in place at least as early as that date. One of the most popular openings in chess today is named after him — the Ruy Lopez.

Since 1886, there have been 48 internationally recognized chess championships and 17 champions. Since every game played in every championship has been saved, data enthusiasts like myself can have a field day analyzing how world championship level chess has changed over two centuries of history.

Perfect Play, Baby

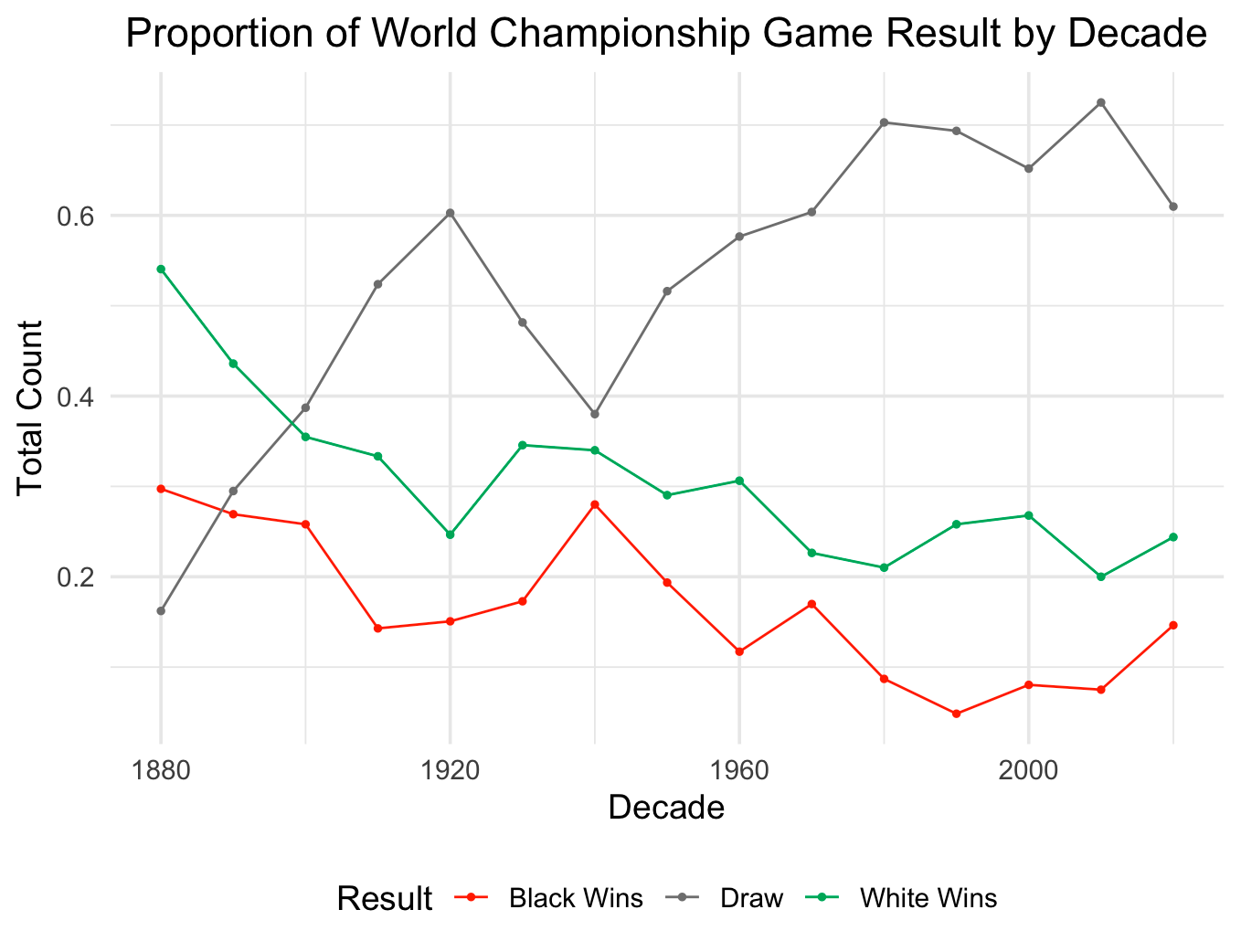

It may come as no surprise that iterations of chess geniuses vying for the championship title have built on each other’s shoulders. This improvement in performance over time is one of the reasons why there have been way less decisive results and many more draws over the decades.

With the advent of computer engines in recent decades, the strongest humans often now train by rehearsing various possibilities with a computer. This helps players get even closer to perfect play — which should always result in a draw. In Magnus Carlsen’s last two championships, 19 of the 24 classical games ended in draws. In the 2021 World Championship, Magnus’ first win was a grueling 8 hour, 132 move game. Not fun.

Strike First, Strike Hard

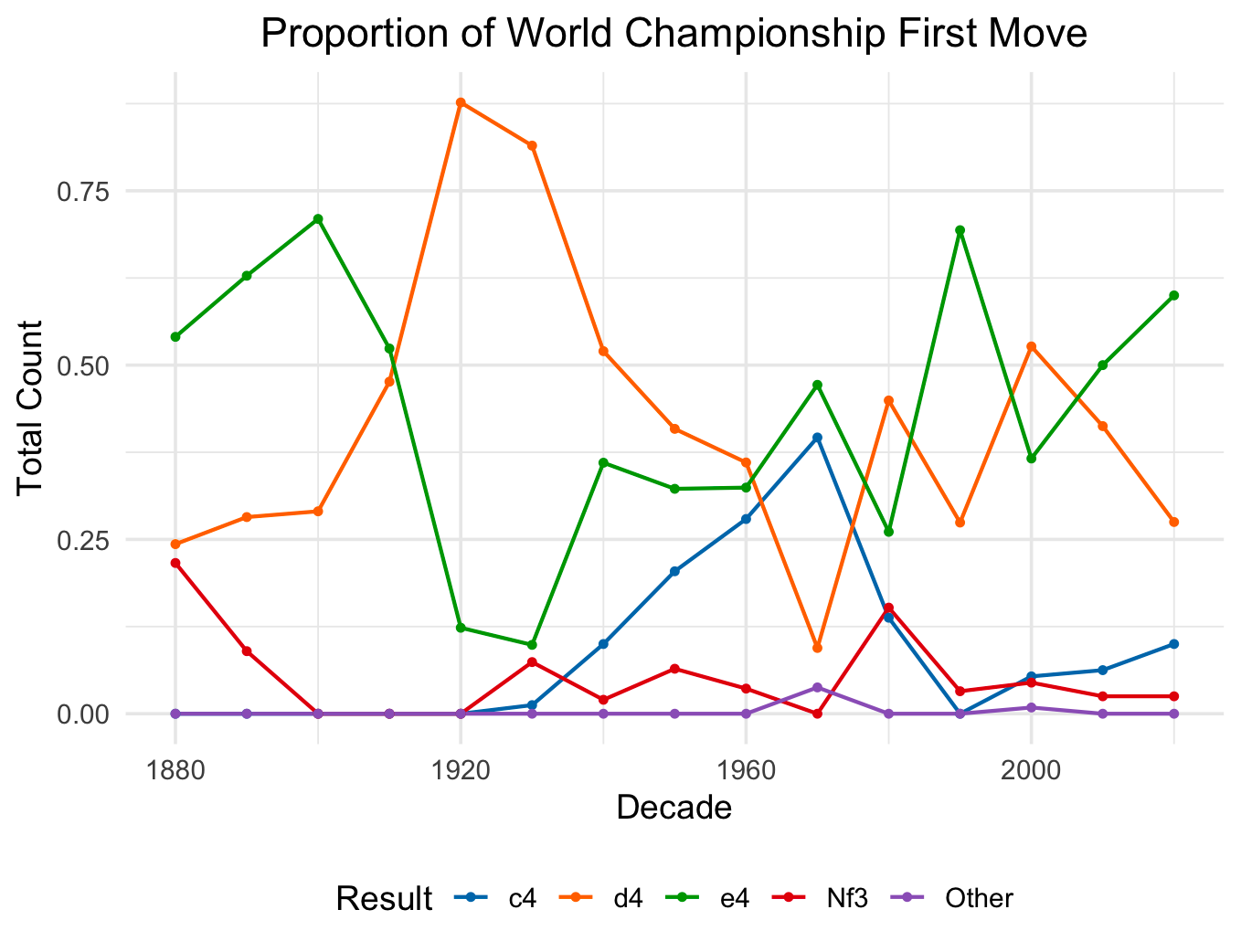

This section may not mean much to my readers who do not play chess, but it is fascinating to track how openings have changed over the decades. Chess players of all levels love studying openings, and world champions are no exception.

Chess, like any part of human culture, has fads. In 1920 we can see d4, or the Queen’s Pawn Opening, was all the rage with more than 90% of games in the decade getting started off that way. We can thank the Cuban champion, Jose Raul Capablanca, for being its biggest advocate back then. The fad slowly died down and e4, or the King’s Pawn Opening, rose back to the number one spot during the 2010’s.

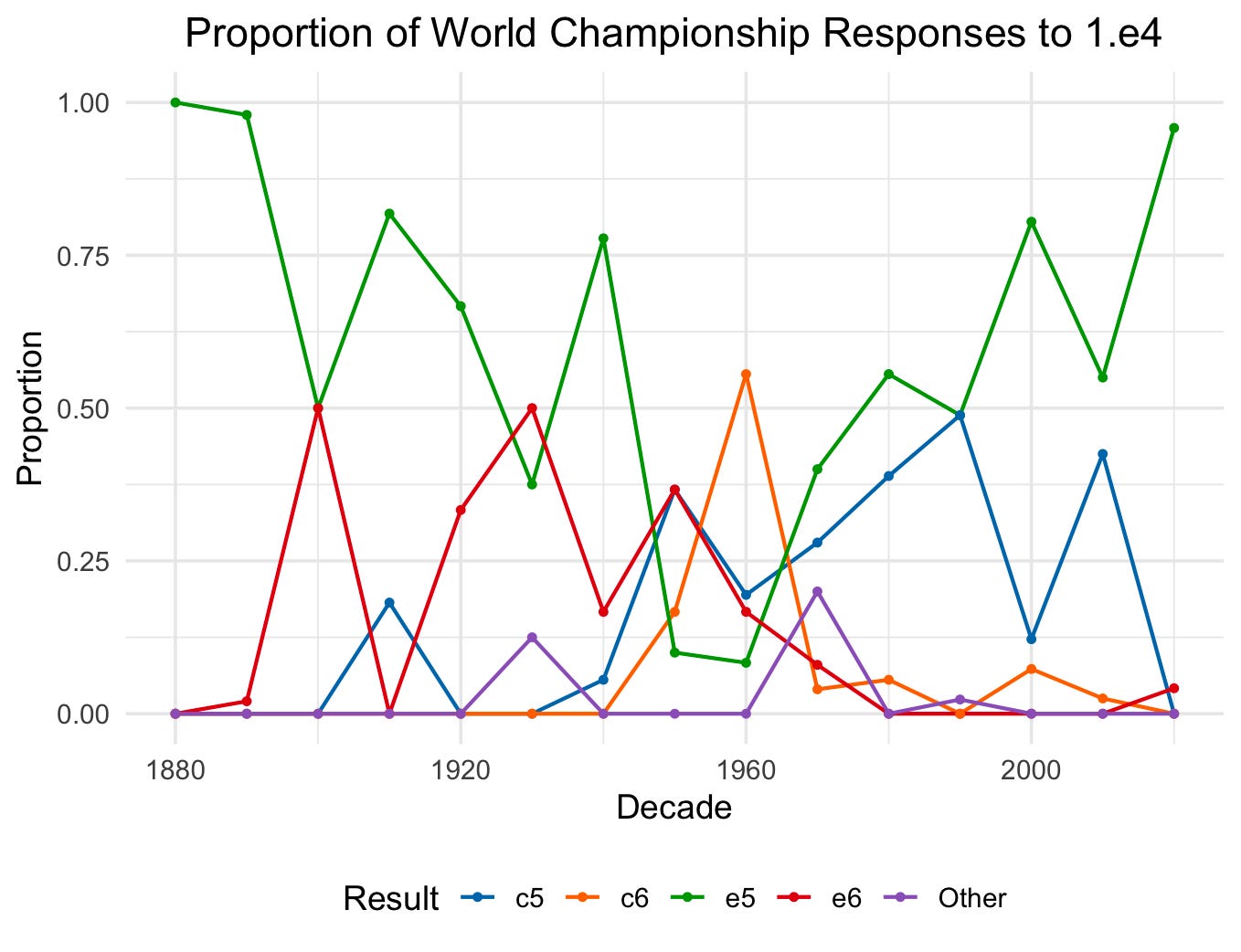

The King’s Pawn opening is naturally more aggressive, but black has lots of interesting and complex responses. Throughout the ages, chess champions have prepared many interesting responses. Kasparov battled his opponents with 1..c5 — the Sicilian Defense, and often won. Challenger Frank Marshall only played 1..e6 — the French — in his 1907 match. Bobby Fischer threw all sorts of weird stuff against Boris Spassky in their famous match in the 70’s: 1…d6 (the Pirc Defense), 1…Nf6 (Alekhine Defense), and 1...c5 as well.

However, our line plot reveals a very sad development in championship chess. 1…e5, the safest and most uninteresting response, has been played 100% of the time in championships in the 2020’s. In a nutshell, that’s because players have used strong computers to basically discredit almost every creative response to 1.e4 at the top level. As a fan (and a lover of the Sicilian defense), I think this means more and more boring games in the future.

Conclusion

In the young Gukesh, I see a beacon of hope for chess championships to come. Gukesh’s style is solid in the opening, but when he sees a chance to win, he pounces. He is not afraid to take risks and has had incredible and exciting results in tournaments in the last couple of years. I am still pumped to follow this event! I’m admittedly biased towards Gukesh and I hope he’ll come ready to play dynamically. Maybe he’ll even play the Sicilian.